German Bibles and the American War of Independence

By Eric Johnson-DeBaufre, Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian

When we think of the influential printed documents of the American Revolution, most of us are likely to name only the Declaration of Independence, that most American of documents with its funny combination of stirring rhetoric and tedious complaint. A few might include Thomas Paine’s revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense, and only a very few would add to the list either Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre or Benjamin Franklin’s repurposed cartoon “Join or Die.”

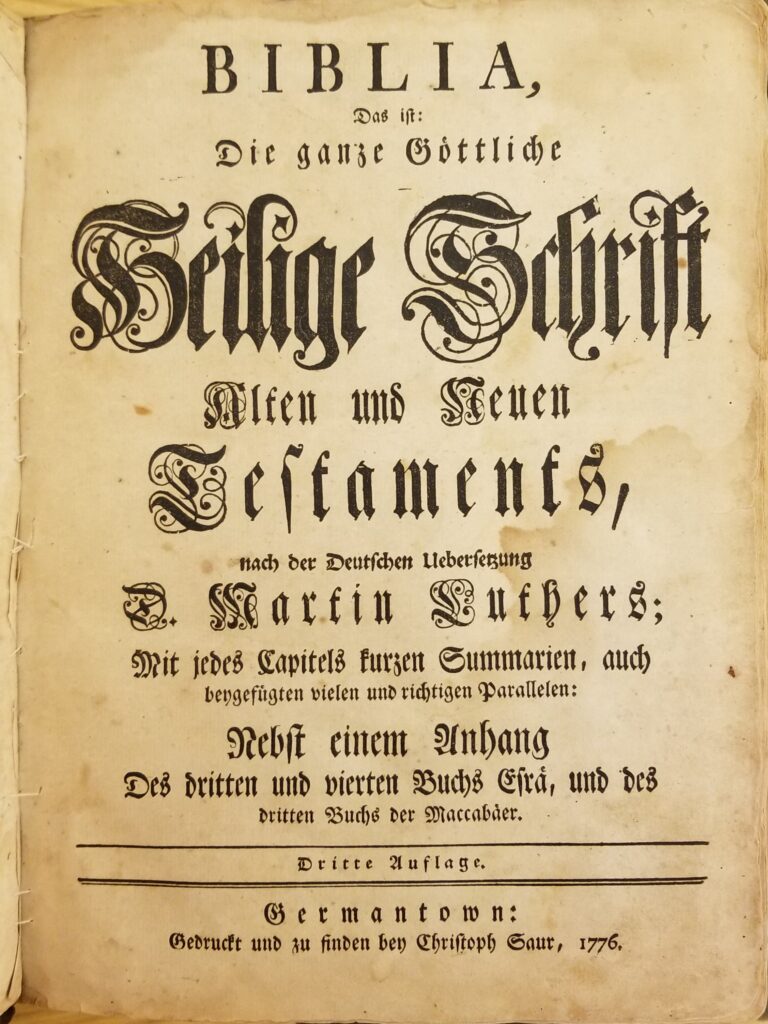

Almost no one, I believe, would think to add Christoph Saur’s German Bible of 1776 to this list, and yet Saur’s Bible played an important role in the British occupation of Philadelphia and in the series of battles that occurred there between 1777 and 1778.

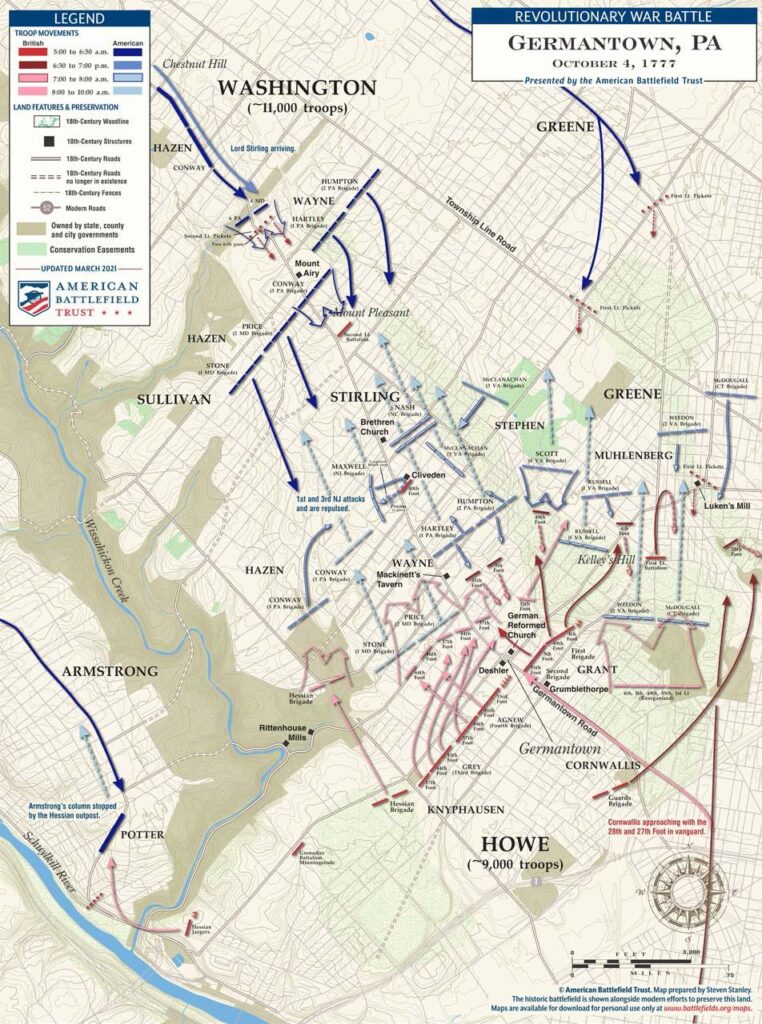

Unlike these other influential printed documents, Saur’s Bible (1776) exercised its power not through stirring rhetoric or provocative imagery but simply by virtue of its materiality. Here’s how it did that. When British troops occupied Germantown in the fall of 1777–an area once separate from the city of Philadelphia but now within the city limits–they established themselves in an area near the German Reformed Church and in a line leading southwest down to the Schuykill River. On the map below the lines and arrows in red indicate the location and movement of the British forces.

On the southwest side of the Germantown Road (now Germantown Avenue) just opposite Grumblethorpe–the summer residence of wealthy Philadelphia merchant John Wister and his family–was the home and print shop of Christoph Saur II. Saur was the eldest son and successor to his father (also Christoph) who had printed the first Bible in a European language in the Americas and whose printing business had become one of the largest in colonial America. In the year prior to the British occupation of Germantown, Saur embarked on the largest printing project in the Americas, a reprinting of his German Bible in an edition of 3000 copies. This was a massive undertaking, involving the labor of many hands and almost certainly multiple presses in order to print the nearly 500,000 sheets of paper that would be needed to assemble these Bibles. Since each of these sheets would have gone through the press twice, that meant approximately 1 million pulls of the hand press were required to bring the project to completion.

By October of 1777, Saur and his workers had finished the printing and had already bound and sold a small number of copies. The bulk of the printed sheets, however, lay in piles in Saur’s warehouse awaiting folding, gathering, sewing, and binding for sale to future customers. When British forces established their encampment in Germantown, they quickly seized the contents of the warehouse and put these printed sheets to a use that would have horrified the pacifist Saur: converting them into powder cartridges for their rifles. The benefit the British derived from this unexpected windfall of “free” paper was enormous: 400,000+ sheets of 15 x 20 inch paper could be converted, if need required, into several million powder cartridges, which would greatly increase the speed with which a rifle could be reloaded. While many of these sheets no doubt went to other sundry (and perhaps even base) uses, knowledge that they had been used by the British for powder cartridges was so commonplace that the third edition of Saur’s Bible came to be known as the “Gun-Wad Bible.” In the end, the British depredation of Saur’s stock proved to be so extensive that fewer than 200 copies of this edition survive.

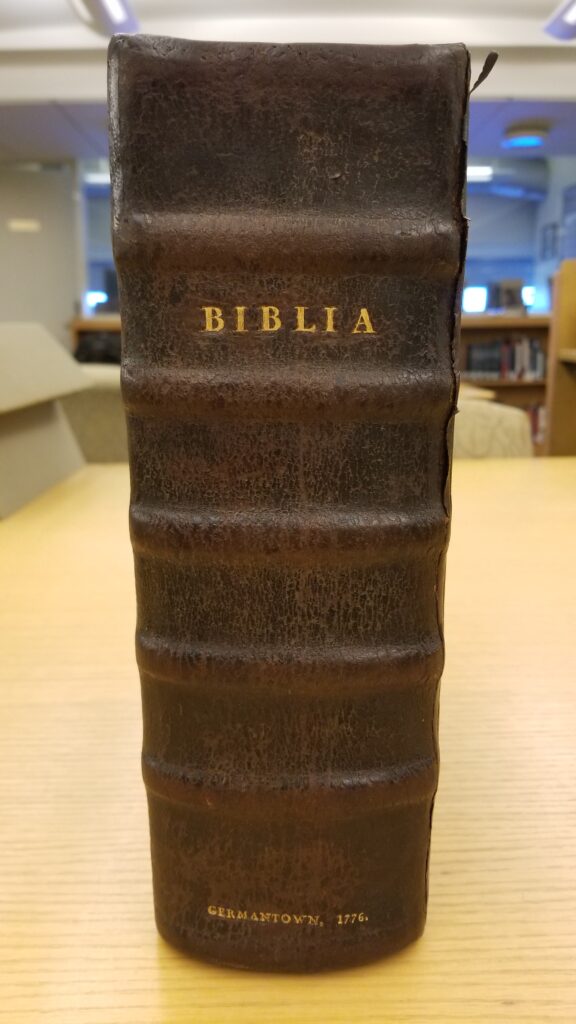

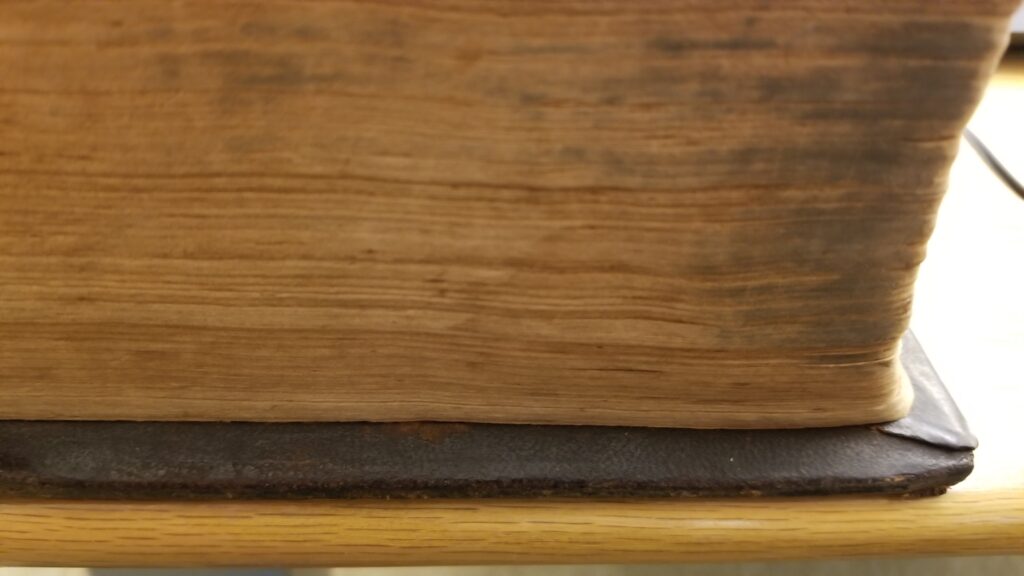

Although Saur’s Bible played a notable if often unacknowledged part in the history of the American War of Independence, I’d like to end by highlighting the ways in which it is also peculiarly but characteristically American. It is American in its very bones: Saur not only cast all of the type in America, he also used paper produced from his own mill on the Schuykill along with ink that he made himself and calfskin native to the region. Its very materiality, in other words, attests to the independent and self-sufficient spirit that was often associated with Americans. And yet it is equally American in being a hybrid. Written in High German and set in Fraktur, the book also displays Saur’s considerable pride in his German heritage by being bound in the traditional German style of the 16th century, with beveled wooden boards covered in calfskin and a heavily corded spine rather than the common American practice of binding with pasted paper boards covered in sheepskin. To a contemporary, the binding of such a book would have immediately stood out as different, as hailing from another place and time. Opening it, the text would have confirmed that impression and signaled to the reader its German-ness. But for anyone familiar with the printer, the book’s use of local materials for every aspect of its production might also have attested to a kind of patriotism or, if not that, at least to Saur’s immense pride in his place. And it is the interplay of these two things that make the book, in my opinion, so distinctly American.

Search by Keyword

Search by day

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

search by month

Search by Keyword

Search by day

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||