Today in History: The Council of Trent and the Regulation of Printing

By Eric Johnson-DeBaufre, Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian

On April 8, 1546, the Council of Trent—formed, in response to the challenges posed by Protestantism, to clarify the doctrines and positions of the Catholic Church and to address calls for Church reform—met for their fourth session in the northern Italian city of that name.

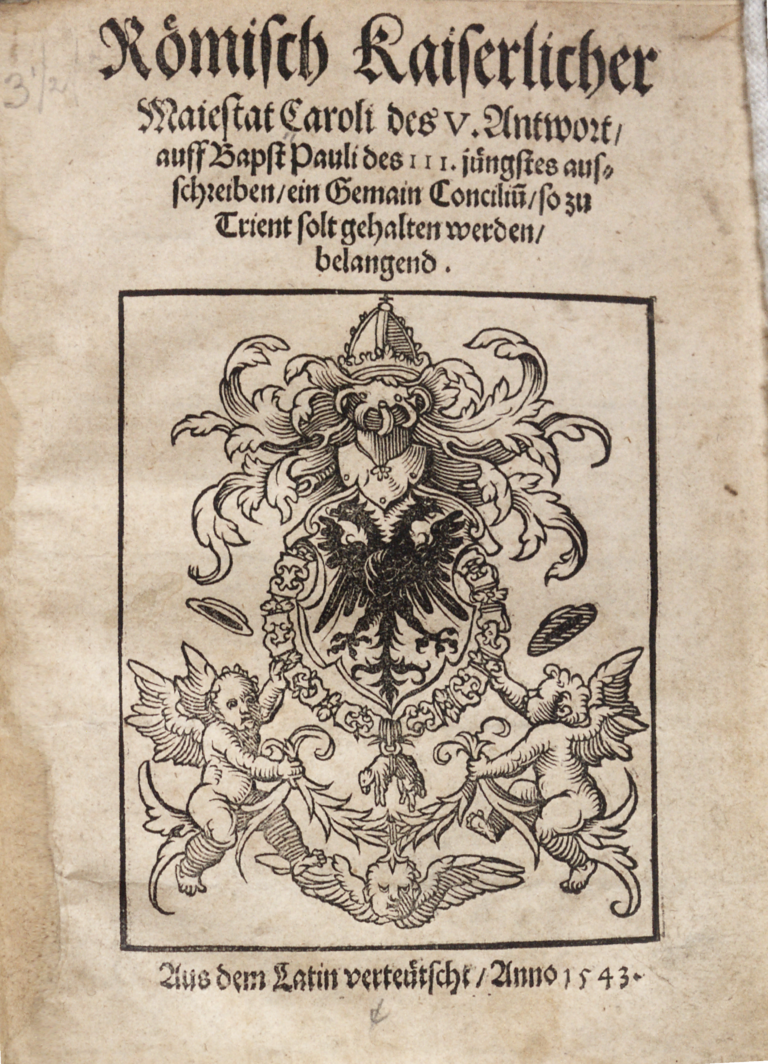

Calls for a general council had, of course, been made since the 1520s.[1] But—as the title page to Charles V’s reply to Pope Paul III (above) makes clear—it was not until the 1540s that an agreeable location could be found, one that would satisfy the Papal states but still appease those who pressed for a meeting in the German lands. Although it lacked a library suitable for the kind of serious doctrinal deliberations that were to occur there, Trent possessed at least two other factors that made it ideal, being close enough to the German territories but still populated by Italians. One hopes that the more moderate delegates to the council might have expressed some objection to meeting in a city that, seventy years earlier, had been the site of a notorious blood-libel trial in which fifteen of the Jews of Trent were burned alive. But whether they did so or not we do not know.

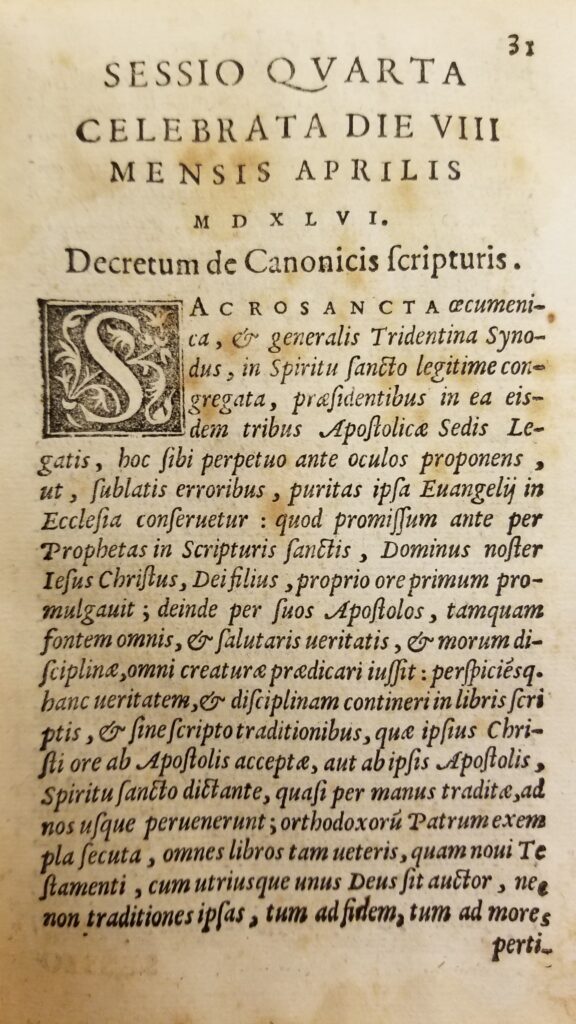

With the location established, the purpose of the April 8th meeting was to ratify two decrees on which the drafting delegation had been hard at work since February. The first and certainly more famous of these decrees addressed itself to one of Luther’s chief contentions: namely, that scripture alone was a sufficient guide for Christian faith and practice. While careful to affirm the truths of scripture, the council’s decree affirmed as well “that these truths and rules are contained…in the unwritten traditions…received by the Apostles from the mouth of Christ Himself, or from the Apostles themselves.”[2] Interestingly, the decree did not specify which traditions the council deemed authoritative but did proceed to list the books it accepted as “sacred and canonical.”

Whereas the first decree sought to clarify a point of doctrine arguably important to all practicing Christians, the second aimed to reform what the council regarded as an abusive practice occurring among a far more limited group—printers. If asked to name the achievements of the Council of Trent, few today would add the regulation of printing to that list, but the decree makes clear that this was a pressing concern:

And wishing, as is proper, to impose a restraint in this matter on printers also, who, now without restraint, thinking what pleases them is permitted them, print without the permission of ecclesiastical superiors the books of the Holy Scriptures and the notes and commentaries thereon of all persons indiscriminately, often with the name of the press omitted, often also under a fictitious press-name, and what is worse, without the name of the author, and also indiscreetly have for sale such books printed elsewhere, [this council] decrees and ordains…

Several things are worth noting here, the first and most obvious being the council’s concern to stop the printing of books on sacred subjects without the permission of ecclesiastical authorities. But what is perhaps more surprising is the council’s interest in regulating the material form of the book and particularly its title-page. No longer, we are meant to understand, would the abusive practice of anonymous publication be tolerated, nor would printers be permitted to omit or disguise (under a false imprint) the name of the press from which a book issued. All of these, according to the decree, would henceforward “appear authentically at the beginning of the book.”

To those of us who take for granted the presence of such information on the title pages of our books, this decree may seem both odd and amusing. But the very idea of the title page, let alone one that more or less resembled the title pages with which which we are familiar today, took many years to develop after the advent of European printing. And even after they became a reliable feature of printed books, printers might, whether by accident or by design, omit information that we today consider essential. As the items below indicate, the suppression of an author’s or printer’s name might appear to be demanded given the content of a particular book and the desire of those involved in its publication to evade punishment.

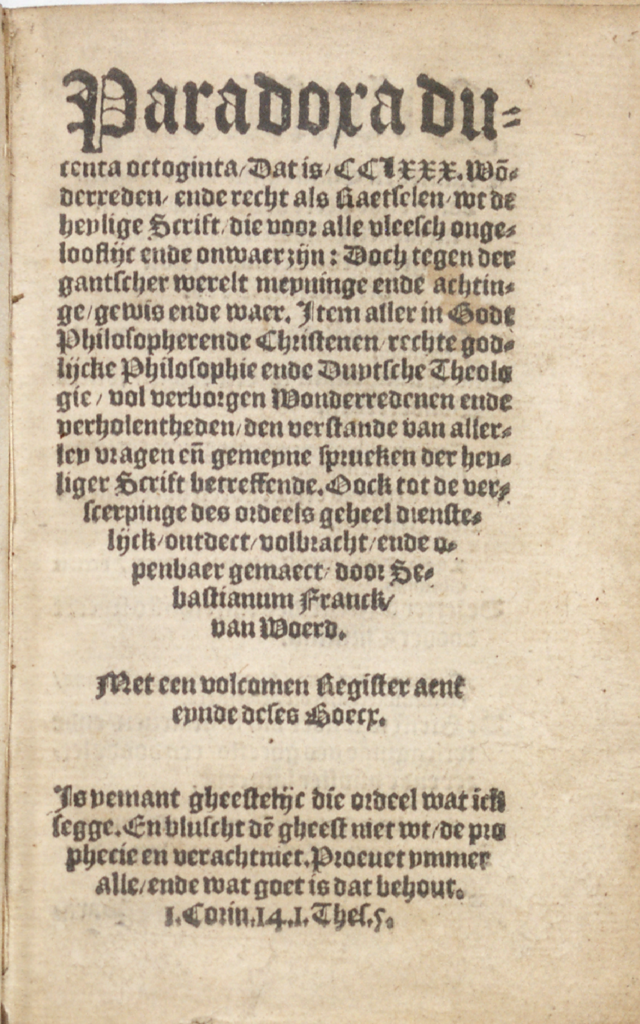

The book on the left, Paradoxa Ducenta Octoginta, was the work of the controversial Reformation figure Sebastian Franck. As Patrick Hayden-Roy relates in Protestants and Mysticism in Reformation Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2019), Franck began his career as a Catholic priest but later “took up Protestant ministry near Nuremberg” (120). Franck’s career within Protestantism proved short-lived, however, as he soon fell afoul of prominent representatives of the movement like Martin Luther. Following his move to the city of Strasbourg, Franck printed and published his Chronica, a work that expressed obvious warmth toward a variety of heretical views and which so offended its readers (including Erasmus) that Franck had to flee to Ulm. It was in Ulm that Franck published another controversial work, the Paradoxa, although no indication of this is given on the book’s title page. Whether or not Franck suppressed this information in the hopes of remaining in the good graces of the city’s officials is hard to determine. If it was a calculated strategy on Franck’s part, it failed, as Franck was expelled from the city in 1539.

While regulating the publication of religious works like Franck’s was the explicit concern of the decree, the Papal authorities may have hoped that by taking such a stand they might also deter the publication of anonymous books like those on the right, books that, while they did not advance dangerous religious ideas, treated religious authorities with ridicule, scorn, and contempt. Celio Secondo Curione’s highly popular Pasquillorum Tomi Duo (Two Books of Pasquils),[3] for example, is just such a work, taking aim not only at the traditional targets of medieval satire such as corrupt monks and priests but also at the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor. Pope Paul III—one of the Council of Trent’s two conveners—is the repeated object of the book’s withering satire, leading one of its contributors to write: Ut canerent data multa olim sunt vatibus aera: / Ut taceam, quantum tu mihi Paule dabis? (“Great sums were once given to poets for singing / What will you give me, Paul, to be silent?”).

Although the Council of Trent clearly had its eyes set on higher things, its interest in regulating anonymous publication helped in some way to stabilize the elements of the title page and thus made a noteworthy if often unacknowledged contribution to the history of the book.

References

[1] For a fuller history of the Council of Trent, including the background leading up to it, see John W. O’Malley, Trent: What Happened at the Council (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

[2] English translation of the Council of Trent decrees is taken from Papal Encyclicals Online. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/councils/trent/fourth-session.htm

[3] Pasquil or pasquinade was the name given to a form of “mocking, clandestine lampoon” of public officials that originated in 16th century Rome but quickly entered the vocabulary of other European languages. The name derived from the practice of people posting anonymous satiric verses—frequently directed at the Pope—on the torso of a classical statue that had been found in the Tiber in 1501 and was erected on a corner near the Piazza Navona. The statue—actually of Menelaus holding the body of Patroclus—was locally known as “Pasquino,” supposedly after a sharp-witted tailor of that name.