Spotlight on Collections: Albrecht Dürer in the Trumbull-Prime Collection

By Eric Johnson-DeBaufre, Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian

In 1905 Watkinson Library received a donation that would be the envy of many museums: a collection of nearly 1500 early printed books and more than 40 scrapbooks of early woodcuts and engravings belonging to William Cowper Prime (1825-1905).[1] Prime—who served as the first chair of Princeton University’s department of art history (a department that he helped to establish) and who was later elected the first vice president of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art—had amassed this impressive collection with the goal of writing a history of early European illustration. Although never completed, Prime’s intended history would no doubt have featured heavily the career and work of Albrecht Dürer, since his collection is particularly rich in both original Dürer prints and in those of the contemporaries and successors who copied and sought to profit from Dürer’s work.

While the presence of so many authentic works by Dürer might mark the Trumbull-Prime collection as museum-worthy and might seem to some to constitute its chief value, Prime’s inclusion of the work of Dürer’s plagiarists and copyists indicates an interest in its educative potential. Indeed, it is precisely this combination that makes it such a valuable teaching collection, especially for students in art history and studio arts. Compare, for example, these two images of Nemesis, both from our collection:

Which of these is an authentic Dürer and which is a copy by the skillful Flemish engraver Hieronymus Wierix?

As the detail at right shows, both images bear Dürer’s insignia, the first in the lower left and the second in the lower right corner. Use of this insignia became the subject of a particularly contentious lawsuit. During his stay in Venice in 1506, Dürer successfully sued the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi over Raimondi’s use of Dürer’s monogram in his copies. The court ruled that while Raimondi could continue to copy Dürer’s images, he could not attempt to pass them off as authentic works of Dürer through appropriation of Dürer’s brand. In this case, the presence of Dürer’s insignia on both prints offers us no guidance in determining the authenticity of one over the other.

A closer inspection of the two, however, reveals that Nemesis 1 possesses much finer detail in the feathering of the wings, as well as a more dramatic sense of contrast between the lights and darks. It is precisely Dürer’s deft handling of light and dark that Erasmus singled out for praise in his 1528 dialogue De recta latini graecique sermonis pronuntiatione (The Right Way of Speaking Latin and Greek), published in the same year as Dürer’s death. Erasmus, speaking in the figure of Bear, says: “I admit that Apelles was a prince of painting and that his rival artists could find no fault with him except that he did not know when to stop….But Apelles used color….Dürer, however, apart from his all-round excellence as a painter, could express absolutely anything in monochrome, that is with black lines only—shadows, light, reflections, emerging and receding forms….above all, he can draw the things that are impossible to draw: fire, beams of light, thunderbolts,…feelings, attitudes, the mind revealed by the carriage of the body, almost the voice itself. All this he can do just with lines in the right place, and those lines all black!”[2]

With Erasmus’s praise ringing in our ears, the choice may seem obvious: Nemesis 1. Nevertheless, it may come as a surprise to learn that the image on the right (Nemesis 2) is, in fact, the authentic Dürer. Students comparing the two images can readily verify this by consulting one of the acknowledged authorities on Dürer’s printed work, such as Joseph Meder’s Dürer-Katalog or F. W. H. Hollstein’s German Engravings, Etchings and Woodcuts, ca. 1400-1700, both of which will confirm that in Dürer’s print the figure of Nemesis faces right.

But despite being correctly oriented, Nemesis 2 lacks some of the striking interplay of light and dark praised by Erasmus, so how can we be sure that it is an authentic work by Dürer and not that of a knowledgeable copyist? It is with a question like this that the Trumbull-Prime collection really shines as a resource for teaching and learning. To answer it, we need not only the help of Meder or Hollstein’s books but also a very close inspection of the print—far closer than one would be allowed if these items were held by a museum but which is not only possible but encouraged at Watkinson Library.

Let’s first compare our copy to an authenticated print of Dürer’s Nemesis (1502) held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

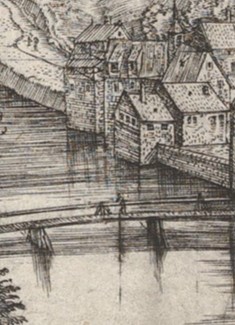

Correctly oriented, the Met’s copy also displays the tonal richness we might expect from an artist like Dürer and that Erasmus prized so highly, so we will want to return to the issue of why our copy differs so drastically. For now, however, we want to focus on a crucial detail in both prints that establishes beyond doubt that they sprang from the same copperplate matrix, that they are, to put it somewhat differently, children of the same mother. Meder and Hollstein alert us to where to look for this detail, which appears only in later printings of Dürer’s Nemesis and in these copies can be seen beneath the bridge spanning the river in the lower part of the engraving.

Clearly visible in both detailed views is a vertical line running just beneath the figure of the man crossing the bridge. That line is notably absent in Wierix’s copy for the very good reason that it was not intentionally placed there by Dürer; it is the result of a scratch made on the copperplate, possibly from a stray piece of walnut shell left during cleaning.[3] In early prints of Nemesis, no such line appears.[4] As a basis for identification, that scratch is as good a piece of forensic evidence as a fingerprint. Moreover, it establishes not merely that these two prints came from Dürer’s press, it establishes the order of their priority.

To understand that we need to return to the question of the reason for the tonal differences between the two copies. In the Met print, the image conforms to the expectations created by Erasmus’s description: striking darks counterbalanced by whites and grays that create contour, depth, and strong visual highlights. Beautiful as it is, our copy lacks many of these qualities because it is a much later impression. As the original copperplate was repeatedly run through the press, it had to be cleaned and re-inked before each new impression. During one such cleaning, a scratch beneath the bridge developed, one that would show up in subsequent printings. But this was not the only change wrought by repeated impressions. With each cleaning and polishing, the fine lines of the engraved copperplate that once held ink and that gave the image its moodiness and drama were worn down, some of them disappearing altogether. The end result was the marked loss of tonal richness so readily apparent when we compare the Met’s copy with ours.

Close examination of this sort is often not possible in museums, which is one of the things that makes the Trumbull-Prime Collection such an incredible resource for teaching and research, especially for undergraduates who may discover through such encounters a career path they might otherwise have never entertained. And it can make possible discoveries that add new knowledge to our understanding of even so well-studied a figure as Albrecht Dürer. Concealed within the paper on which our copy of Dürer’s Nemesis was printed—and visible only through the use of a backing light—is a watermark that places the printing of our copy more than a decade after Dürer’s death.

Meder’s Dürer-Katalog identifies this as watermark number 296, which, according to authorities on watermarks (e.g. Briquet), first appears on some European papers between 1540 and 1550. Although Meder notes the appearance of this watermark on other late impressions of works by Dürer, he does not record any instances of it for Nemesis. Our copy is thus proof of the enduring interest and value that this Dürer masterwork held for at least one customer more than forty years after its first publication. However small, discoveries like this enrich our understanding of the continuing esteem in which Dürer was held in the years following his death and add to our knowledge of his works’ publication history. And they are enabled by the kind of hands-on examination encouraged at Watkinson Library.

References

[1] Marian G. M. Clarke, David Watkinson’s Library: One Hundred Years in Hartford, Connecticut, 1866-1966 (Hartford, CT: Trinity College Press, 1966) p. 76.

[2] Desiderius Erasmus, “The Right Way of Speaking Latin and Greek: A Dialogue” (trans. Maurice Pope) in Collected Works of Erasmus, vol. 26 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985) p. 399.

[3] A close examination of Wierix’s print reveals no trace of the man on the bridge either.

[4] See Meder 72 in Joseph Meder, Dürer-Katalog (Wien: Verlag Golhofer & Ranschburg, 1932); cf. Hollstein 72 in F. W. H. Hollstein’s German Engravings, Etchings and Woodcuts, ca. 1400-1700: Volume VII, Albrecht and Hans Durer (Amsterdam: M. Hertzberger, 1954).